July 22, 2023 The Press_Te Matatika/ Korea 70 years on: Veterans remember the war that’s never ended

- Writeradmin

- Date2023-07-22 00:00:00

- Count3327

- URL https://www.thepress.co.nz/a/nz-news/350037731/korea-70-years-veterans-remember-war-thats-never-ended?fbclid=IwAR1sTyTnkxumISHO2vjZkqdLXgau0b6SSj0-TiZWn2WurkPQrv7MQFvGWhI

Korea 70 years on: Veterans remember the war that’s never ended

Ahead of the 70th anniversary of the Korean War Armistice on Thursday, reporter Shannon Redstall explains why this conflict shouldn’t be considered “the forgotten war”.

When the clock struck 10pm on July 27, 1953, Allied soldiers south of the 38th Parallel launched flares into the night sky. No longer hiding their positions from the fierce North Korean Army, they fired a shower of lights, not bullets, to celebrate the signing of a peace treaty, a formal armistice after years of bitter, bloody war.

For Canterbury veteran Forbes Taylor, this remarkable experience came just weeks into his deployment to the front line of the Korean War and has stayed with him for 70 years, a moment of levity amid the brutality of a war he now sees as “totally wrong”.

Almost 10,000km away, a young Victor Pidgeon had not long returned to New Zealand after his 18-month deployment. He was battling a nasty bout of malaria, an unwanted souvenir from his time fighting the communists.

These two men were among the more than 6000 Defence Force personnel who served in the Republic of Korea under a United Nations flag between 1950 and 1957. It’s estimated only 191 are still alive today - including Pidgeon and Forbes.

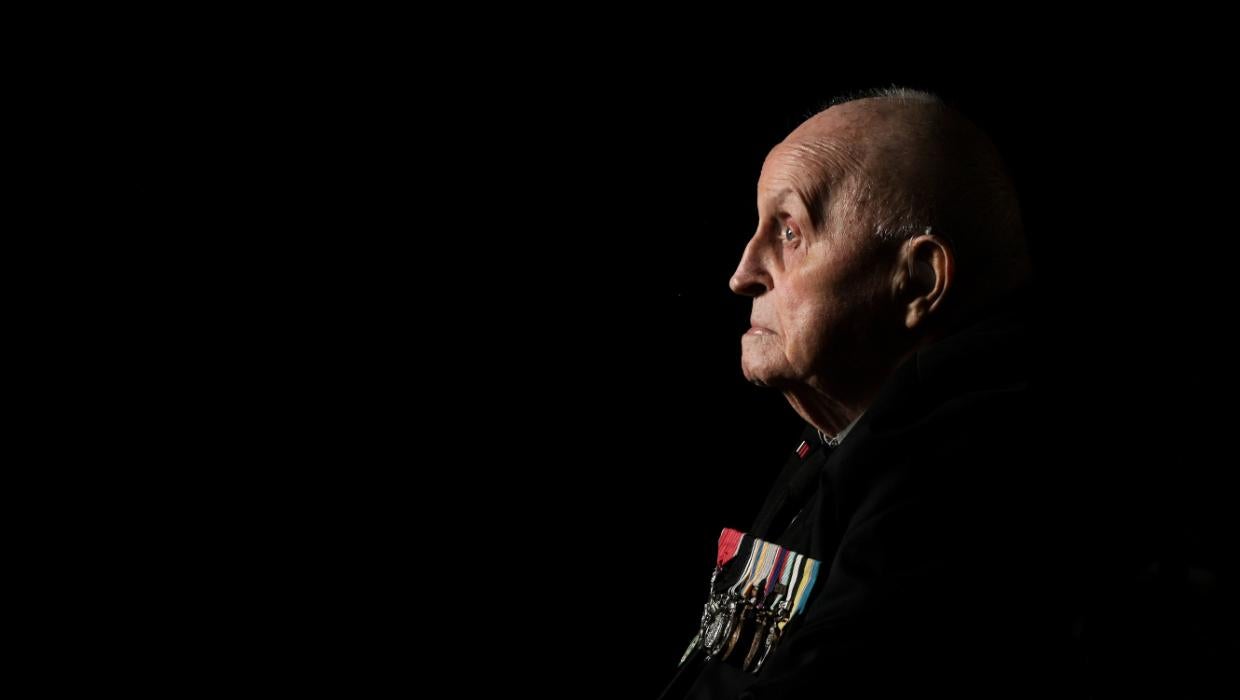

Victor Pidgeon, 96, is a Korean War veteran from Christchurch who served as a driver in the New Zealand Army. Photo by Chris Skelton/The Press

Victor Pidgeon, 96, is a Korean War veteran from Christchurch who served as a driver in the New Zealand Army. Photo by Chris Skelton/The Press

Shortly after 135,000 North Korean soldiers crossed into the territory of their southern neighbour on June 25, 1950, New Zealand was one of the first countries to answer the call.

It took just three days for the Korean People’s Army (KPA), backed by the Soviets, to capture Seoul and for the United Nations Security Council to adopt Resolution 83, asking its members to help rescue the Republic of Korea from the jaws of defeat.

Prime Minister Sidney Holland quickly announced that two Loch-class frigates, HMNZS Pukaki and Tutira, would be made available, just the fourth time Aotearoa would contribute to a foreign war. They departed Auckland just eight days after Kim Il-sung’s invasion began.

Before the navy even reached its destination, the KPA had advanced halfway across the country.

The quickly deteriorating situation led New Zealand to offer 1000 ground troops to the UN Command, ahead of assistance from Australia, Canada and even the United Kingdom.

Enthusiasm was widespread, with 5982 men enlisting for Kayforce, as it would become known, almost six times the number required.

Crowd at Aotea Quay, Wellington, as Kayforce troops leave for Korea on the Ormonde in December 1950.

Crowd at Aotea Quay, Wellington, as Kayforce troops leave for Korea on the Ormonde in December 1950.

UNKNOWN NZ ARMY PHOTOGRAPHER / ALEXANDER TURNBULL LIBRARY

The turning point of the war came in mid-September when America’s General Douglas MacArthur actioned Operation Chromite, the bold but extremely risky amphibious counter-offensive behind enemy lines in Incheon Harbour, near the capital, Seoul.

The New Zealand frigates helped to carry the attack force and then formed part of the “Iron Ring” closely guarding Seoul from the harbour.

Within the month, the city had been returned to South Korea, marking the United Nations’ first military victory against an outside aggressor.

The war could have ended there, but, eager to make good on the UN’s intention to unify Korea, the United Nations forces pressed into North Korea, drawing China into the conflict.

As promised, New Zealand’s 1000-strong “Kayforce” landed in the southern city of Busan in January 1951.

Twenty-four-year old Victor Pidgeon had hoped to be part of that force. He was fed up with his job as a fireman in the railways and his overly sarcastic boss. So when he was initially told no, he couldn’t leave the railways to join Kayforce, it only sharpened his resolve.

“I went back to the railway office and I said, ‘Oh, I forgot to tell you. I’m going into the army in a fortnight’s time’. ‘You can’t do that!’ they said. ‘I can, you know’, because I was going to leave if they had’ve stopped me,” he recounted with a grin.

Korean War veteran Victor Pidgeon during his time working as a driver between 1951 and 1953. (Supplied photo)

An initial flash of panic had him asking, “What on Earth have I put my name down for?”, but the pull of an international adventure was much stronger.

Pidgeon initially trained to be an infantryman at Burnham Military Camp, but the demands of the war saw his lemon squeezer swapped for the beret of a driver, a change he now sees as lucky, for him personally but also for the country.

New Zealand never had any infantry fighting in the Korean War, and it’s part of the reason our fatality rate was much lower than that of other countries.

Opposition leader Walter Nash was at the dock to shake the hands of the divisional signallers and transport company boarding the TSS Wahine as part of the first reinforcements in August 1951.

The steamship had only made it as far as the Wellington Heads before it turned back. A pilot boat came out to meet the ship and took a boy off. His parents had spotted him on the deck and notified the harbour master, who let the Wahine know quick-smart that the lad was under age.

Korean women and children search the rubble of Seoul for anything that can be used or burned as fuel in the Korean War. (Photo: US National Archive)

The arrival in Busan was less than heartening. Poverty was widespread as North Korean refugees had flooded the city, people sitting in rags among makeshift houses alongside rat-infested open sewers.

Driving north towards the front line, things didn’t get much better. Fourteen months of war had ravaged the country.

“It was just a barren country, really … no trees, and you didn’t see many animals,” Pidgeon recalled.

He was stationed near the Imjin River, which he said reminded him of the Waimakariri River back home. Pidgeon spent his time driving around supplies, shells and rations - and a particularly difficult English major.

The summers were stifling and the winters were bitterly cold, with the temperature struggling to get above freezing during the day.

“If you threw a cup of water up on the tent, it wouldn’t come back. It would freeze as soon as it hit,” Pidgeon laughed.

A satisfied bunch of Kiwis outside a mess tent after Xmas dinner at 163 Battery in December 1951

A satisfied bunch of Kiwis outside a mess tent after Xmas dinner at 163 Battery in December 1951

IAN MACKLEY / ALEXANDER TURNBULL LIBRARY

Speaking to him, you get the sense that he quite enjoyed his time in Kayforce. The camaraderie among the United Nations soldiers was strong, the beer was cold and contributing to helping get the country back was fulfilling.

But the reality of the war was never far from his mind.

It’s estimated 85% of North Korea’s buildings were destroyed in the war, becoming one of the most heavily-bombed nations in the world.

The US dropped more bombs, including more than 30,000 tons of napalm, on Korea than it did across the Pacific during all of World War II, according to academics.

“Some of them, poor devils, you know, had it hard … We were lucky that we were drivers, in the end. If we’d have gone as infantry, we would have been right up in the front,” he said.

One of Pidgeon’s closest calls was on board the HMNZS Rotoiti after it crossed the 38th Parallel and entered North Korean waters.

Despite being an army man, the eager young soldier had volunteered to be part of an exchange with the navy. He was one of six men chosen to temporarily join the crew of the New Zealand frigate.

“We were up there, next thing the shells started landing, getting pretty close to the Rotoiti, so they slipped the anchor,” he said.

Pidgeon was helping the gunners out, handing up shells to load, and said the enemy fire got to within around 20 metres of the ship.

“They were getting pretty close. That’s why they got away in a hurry,”

Australian and NZ personnel outside Anzac Park, a playing field they built alongside forward defensive positions.

Australian and NZ personnel outside Anzac Park, a playing field they built alongside forward defensive positions.

IAN MACKLEY / ALEXANDER TURNBULL LIBRARY

In April 1951, New Zealand gunners achieved their most celebrated victory of the campaign, the Battle of Kap’yong, for which the regiment was awarded a South Korean Presidential Citation.

Following the collapse of a South Korean division, the 16th Field Regiment played a vital support role alongside Australian, Canadian and British battalions against the Chinese Army. It was during this clash that Kayforce suffered its first battlefield casualty.

Second Lieutenant Dennis Fielden was shot in the back of the head by a bullet during a sudden Chinese attack.

Later that year, Cabinet approved a relief scheme that allowed the original volunteers to be replaced. This came as a relief for many on the ground, as the monotony of what had become relatively routine operations led to waning enthusiasm.

Nine hundred men were drafted and arrived in Korea in 1952, and more followed in 1953.

Spirits were high, drinks flowed and the Wakanui Community Hall near Ashburton was packed as the district threw a party to send its only Kayforce soldier, 21-year-old Forbes Taylor, off to war.

Taylor came from a strong military background. His father had survived the Battle of Passchendaele in World War I and his eldest brother was a member of the RNZAF.

Following the early death of his father, and the loss of his eldest brother in a tragic motorbike accident, Taylor was trying to run the family farm with his mother when he was called up for compulsory military training.

It was at the army office in Ashburton where he first saw the enrolment form to volunteer for Kayforce. Missing his father, Taylor said he “had to get away and do my own thing”.

After six weeks of basic training at Burnham as part of the sixth reinforcement, Taylor was trained as part of the Signals Corps and then selected to attend a Kayforce Officers training course at Waiouru Army Camp in the North Island. Of the 400 men who trained in his reinforcement at Burnham, Taylor was the only one to rise to the rank of lieutenant.

By 1953, when he arrived, Seoul was a city of rubble.

From his perch on the back of a store truck, a wide-eyed Taylor took in the shacks shaped out of ruins and the Korean people trying to make a living from makeshift roadside stalls.

Nothing was higher than a single storey and the central train station, which is still standing today, was one of the only buildings to have survived years of intense fighting.

“I don’t think there was a building there that wasn’t burnt out or generally smashed up. [Seoul] suffered terribly in the war,” Taylor said.

“A lot of the buildings were built out of grass cuttings and to keep warm in winter, they ran the chimney from where they cooked, right under the floor, to the other end of the house and they let her into the house. The winters there were absolutely appallingly cold.”

Ninety-one-year-old Korean War veteran Forbes Taylor, who was a second lieutenant in Charlie Troop.

Ninety-one-year-old Korean War veteran Forbes Taylor, who was a second lieutenant in Charlie Troop.

CHRIS SKELTON / THE PRESS

Taylor was stationed with Commonwealth Signals Regiment Charlie Troop, along the front line in much of what is now the Demilitarised Zone. He was responsible for laying out 2400km of physical telephone and radio lines alongside land mines and towering layers of concertina barbed wire.

“At maximum effort we could have around 280 guns firing onto four or five acres of land,” Taylor said, recalling instances where thousands of Chinese soldiers were killed in a night near Hill 355.

The heavily fortified hilltop position was chosen for its ability to dominate the valley below, but it left Taylor and his fellow signalmen exposed to enemy fire.

Trudging up the hillside on a hot summer’s day, the armoured jackets and tin hats often got ditched as carting the repair equipment took priority.

Shelling came as close as 30 metres, Taylor said.

“Of course, we never actually knew when the hell they were going to come or exactly where they would land!”

The greatest risk was the land mines - explosive devices that would detonate after they were stood on. After the armistice, their danger grew as previous barbed wire demarcation lines rusted away.

One evening, Taylor was out fixing telephone lines. In the morning he asked an engineer to come back to the spot and see if the area where he was digging was safe.

“He used a very thin bayonet that he put in the ground at an angle and he showed me where I had been the night before, one foot from one of these mines!”

While Taylor’s life had been spared by his fortunate choice of footsteps, other members of his troop weren’t so lucky. Two men in his 120-strong troop were killed by land mines, and one man lost his legs in an explosion, he said.

“Shocking things,” Taylor recalled.

It’s estimated 800,000 land mines still lie along the Demilitarised Zone, with civilians continuing to be injured and killed. In 2022, Korean media reported a man in his sixties was killed after monsoon rain uncovered a mine.

Forbes Taylor, of Christchurch, when he served in the Korean War as a second Lieutenant to Charlie Troop in the Signals Regiment. (Supplied photo)

Forbes Taylor, of Christchurch, when he served in the Korean War as a second Lieutenant to Charlie Troop in the Signals Regiment. (Supplied photo)

Being an officer had its privileges, like having a tent to yourself, but it also had its pitfalls and Taylor said the worst thing was writing to the families of those who died.

He would take time to explain not only what had happened, but what a great person they were and how much they would be missed. He said it was difficult because “unless you’re in it, you’ve got no idea what it’s like”.

It came as a surprise to the ground troops when the armistice was finally signed on July 27, 1953, three years and a month after the war began. Peace talks had been under way for more than two years but Taylor said he and his troop were unaware of the progress until they were told all hostilities would cease at 10pm.

“They fired all those lights up into the sky, and it was quite a remarkable experience,” he said.

But despite the celebration, the plight of the Korean people .

Men from Charlie troop, Royal NZ Signals Regiment, laying telephone cable in Korea in 1952.

Men from Charlie troop, Royal NZ Signals Regiment, laying telephone cable in Korea in 1952.

UNKNOWN NZ ARMY PHOTOGRAPHER

It’s estimated around three million Koreans from both sides, including one million civilians, were killed in the conflict, a higher per capita mortality than either World War I or World War II.

Hundreds of thousands of Chinese soldiers, around 37,000 Americans and 45 New Zealanders lost their lives.

The majority of Kayforce left Korea in November 1954, with the last troops returning home in July 1957. New Zealand had a naval presence, as part of the British Far Eastern Fleet, until the same year.

New Zealand was represented by a military liaison officer as part of the Commonwealth Liaison Mission in Korea until 1971, and since 1988 around a dozen Defence Force personnel have been posted to the United Nations Command near the border with North Korea.

The war had a lasting effect on our foreign policy, and helped New Zealand secure a long-coveted security commitment from the United States. In September 1951 the Australia New Zealand United States (ANZUS) Treaty was signed.

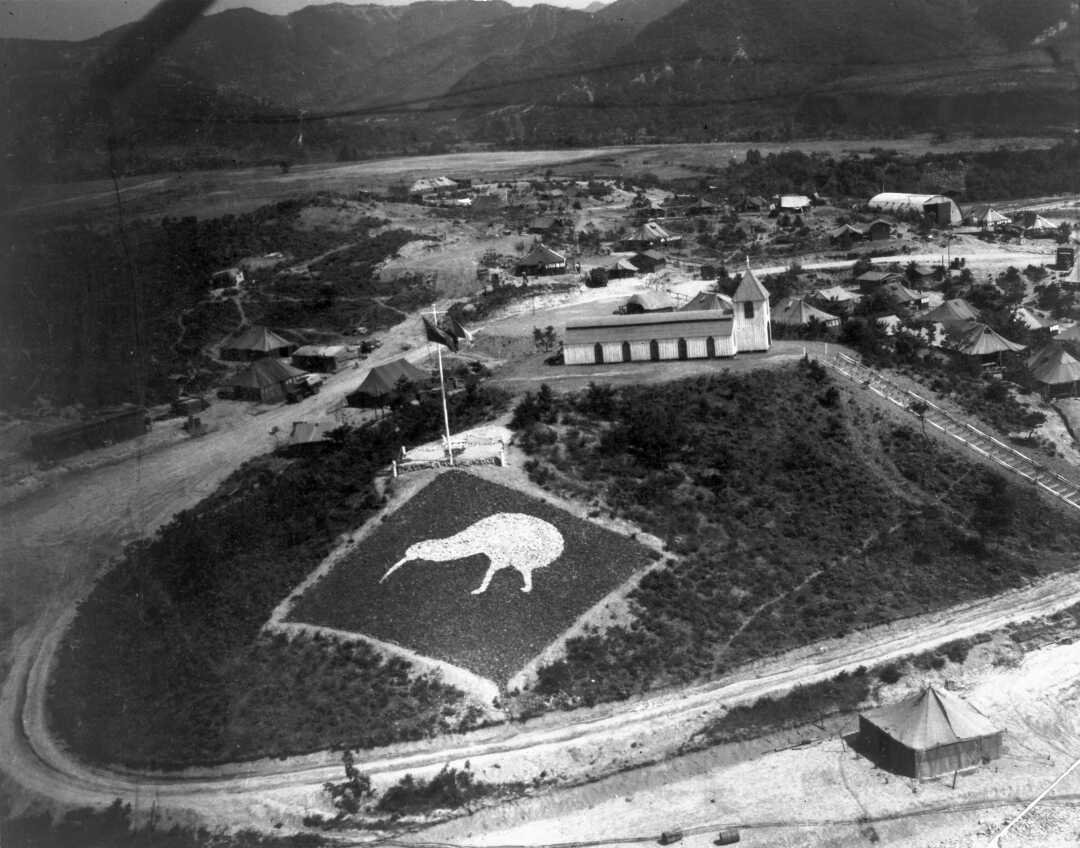

Headquarters of 16 NZ Field Regiment in Korea, with a kiwi symbol made out of painted rocks. (Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library)

Headquarters of 16 NZ Field Regiment in Korea, with a kiwi symbol made out of painted rocks. (Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library)

Thursday will mark the 70th anniversary of the Korean War Armistice, and celebrations will be held around New Zealand to commemorate its signing. In Auckland, a commemoration service will be held at the Korean Memorial Stone in the Parnell Rose Gardens.

In Christchurch, a private service will be held for the veterans and their families on July 29. South Korean ambassador Kim Chang-sik is making the journey to the Garden City especially.

In Korea, two days of commemorations are planned in the wartime capital of Busan, in the south of the country. Governor-General Dame Cindy Kiro will be travelling to Korea for the occasion.

As New Zealand’s head of state, she will be the highest-ranking official present from any of the 16 nations represented. She is expected to give a keynote speech at the “thank you banquet” for the veterans and their families, as well as to lay a wreath alongside South Korean President Yoon at the United Nations Memorial Cemetery in Busan, where 33 Kiwis are buried.

A group of New Zealand veterans and their families will also be travelling to Korea for the occasion. The Revisit Korea Programme is a longstanding commitment from the Korean government to the nations who contributed to the war effort.

Every year a number of veterans and their families are flown to Korea and hosted on a week-long programme which includes visits to the Demilitarised Zone, Korean War Memorial and the United Nations Memorial Ceremony.

This year five New Zealand families will be represented, including two veterans themselves.

Both Taylor and Pidgeon have returned to Korea through this programme.

“It was wonderful, really. They treated us like kings,” Pidgeon recalled of his trip in 2013. “It was just like coming back to your old home town.”

Both men remarked on the phenomenal progress the country had made in the decades since the armistice; 30 bridges over the Han River when there used to be just three, staying in room 2037 in a city where there had previously only been single-storey buildings.